Sewing machine project makes history books come alive

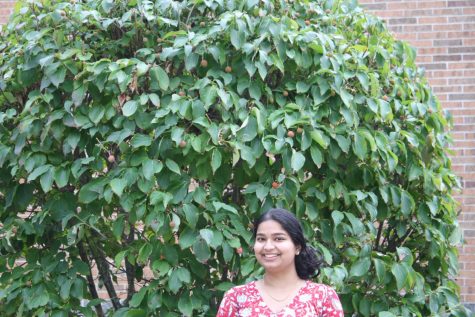

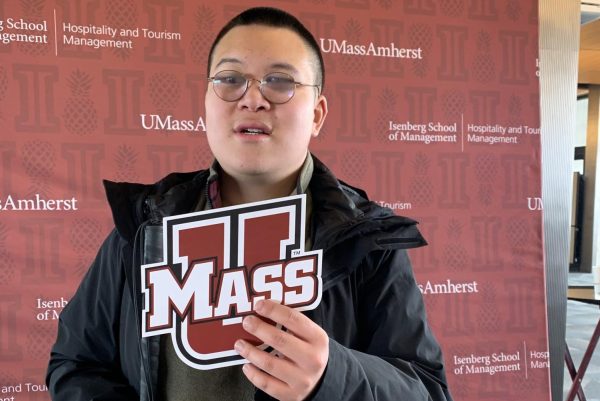

Scully’s compilation of Singer sewing machines from 1800’s to 1900’s

September 24, 2021

Deep in the factories of the industrial revolution, workers toiled away on Singer sewing machines for long hours and uncertain pay. Nearly 200 years later, those same machines will be wielded by high school students, who will gain a deeper understanding of the possibilities of these machines and the struggles those workers faced.

This January, history teacher Stephen Scully will execute a sewing machine project for his U.S. history students to experience their history lessons firsthand.

The idea of the project came to Scully toward the beginning of the pandemic, as he searched for ways to make students feel more engaged during online classes. Especially as someone who has done similar history projects over the course of his career, Scully wanted to create a meaningful experience for students that could be connected to society and the pandemic. Over the past year, Scully has been curating a class set of Singer sewing machines that were used during the Industrial Revolution.

“I am a firm believer that in order to get kids to buy what I’m selling, to get kids engaged in history, you have to put them back in the moment. You have to try to take them back in time like putting them on an antique sewing machine,” Scully said.

Scully chose to work with sewing machines because he has been collecting them for over twenty years, and he knew more were still in existence around New England for him to acquire. He also wanted to choose a simple machine from the revolution so that students could manipulate and connect with the revolution.

“I’ve been collecting antiques for probably over twenty years. I knew that they were out there. So I knew I could secure them. So that was a big factor. The machines are also simple, so kids will be able to learn something new without being overwhelmed,” Scully said.

The machines are all the same, flywheel-type machines, ranging from the late 1800s to the 1920s.

“It doesn’t get more authentic. You’re having the same experience as somebody who worked in Mills, or a tenement house 100 years ago,” Scully said.

Overall, Scully’s U.S. History students will spend one week learning about the basics of the revolution and one week with the machines, focusing on Industrial Revolution culture and the function of the flywheel, an industrial revolution that rotates to power machinery. Scully hopes to assign a culminating project for his students relating to the machines, which he is in the process of planning.

After having taken classes over the summer on machine restoration, Scully spent his summer searching for machines and restoring them for his students to use effectively. Then, he found a group of volunteers who knew how to sew to help him with the project after some further training. Volunteers will practice in the coming months, in order to help students in January.

“I am a novice, but I am bringing together experts,” Scully said.

In addition, Scully will be receiving the help of his former students for this project, like senior Erin Fraser. Fraser began her journey with her former teacher because she has always liked sewing and the history of older machines, and after finding out that Fraser knew how to sew well, he offered an opportunity to help with his sewing assignment.

“I have also been working on diagrams and videos pertaining to the treadle machines that Mr. Scully can use in class to help teach the kids about the machines as well as how to use them,” Fraser said.

One of Scully’s adult volunteers, Nancy Beckwith, grew up with these types of machines, ushering her to take part in Scully’s project.

“It piqued my interest because when I was a young girl, my grandmother had a travel machine. Then it was left to me, so I had had it for quite some time. The project reminded me of my grandmother and how I used to sew with her, so it spurred some wonderful memories in my life I wanted to share,” Beckwith said.

However, the process of working with the machines and finding volunteers wasn’t always so streamlined. Scully experienced a variety of setbacks in both the restoration process as well as in the volunteer search and training. Most of the machines needed parts reworked, and Scully found it difficult at times to curate a set of finished machines.

“I would drive long hours from Rhode Island to Manchester to seek out people who could donate machines, and they were all needing refinishing. For example, a vendor I went to would refinish the cast iron legs, all the wood, put new belts on, and then a handful of the machines would then have problems with the internal works of the mechanics after refinishing due to interferences with the parts,” Scully said.

Nevertheless, despite such challenges, Scully is grateful for being able to create a project on such a scale that he believes will catalyze his own growth as a teacher as well that of his class by making history come alive.

“These are the kinds of experiences that the kids will remember, they may not remember most of what I say regarding the Industrial Revolution, but they will remember sewing and antiques and your sewing machine. I’m trying to sell kids something that they often don’t see the connection to their lives,” Scully said.

Scully hopes for students to not only learn about the mechanics of the machines, but he also hopes for his class to have a shared experience with the workers of the 1900s via human power.

“So I want them to learn about the flywheel and how it transfers power and balances power. I want them to connect with an age when there was no electricity in factories. And the power was human power. And so you would bring the power and that in the level of difficulty that that brought to the, to the workplace in on the individual and the impact that he had. So those are some of the lessons that I want kids to experience, I want them to be sore,” Scully said.

Volunteer Beckwith especially looks forward to seeing students experience the machines and get a better idea of the tasks workers engaged in, especially in the factory conditions of the time period.

“I’m looking forward to seeing how the students react to the fact that there were actual workers that use this machine to produce something in a production level. It will be cool for kids to see. It wasn’t all fancy and fun, it was long hours and tough,” Beckwith said.

After immersing themselves in the past, Scully strives to have students make connections to the present day. Coming full circle, he wants students to empathize with the individuals today using the machines in underdeveloped countries.

“No, we’re not the industrial manufacturing power we once were. But there are people that are on machines, making your clothes right now, somewhere. And maybe they’ll have more empathy for what those folks are going through,” Scully said.

Echoing Scully’s goals for his project, volunteers like Fraser are excited for learning the mechanics of older technologies and getting to partake in her hobby in a way that has roots to the past.

“Something that piqued my interest the most was just getting to know how to use the machine and how different it was to other sewing machines I have used before,” Fraser said.

Although Scully has never done something of this scale before and he isn’t sure whether or not the project will finally work out, he credits the experience as one that imparted valuable lessons.

“This project has been great for me and my class. […] And so sometimes it’s a leap of faith, right?” Scully said.

Donna Aybar • Oct 1, 2021 at 9:37 am

If you haven’t, you must read The Sewing Machine by Natalie Fergie. I use a 1946 Singer Featherweight, and a friend gave the book to me as a gift. I’m reading it right now and think the teachers in your Language Arts dept might team with you on an interdisciplinary unit! You should contact the author and see if she would Zoom your classes! Before I retired I taught an interdisciplinary unit on quilting and the history of the underground railroad.

As a life long sewer and quilter, this is very exciting to me and I would love to hear how this experience goes for you and your students.

Much luck to you!

Donna Aybar