When most people think of Westford Academy Theater Arts (WATA) Artistic Director Michael Towers, the words “director” and “teacher” immediately come to mind. Recognized as the talented director of many of WATA’s award-winning productions and a guiding hand in theater education, Towers has made a lasting impression on Westford Academy over the last 26 years. However, throughout his time at WA, Towers’ impact on productions has run deeper than solely the directing process.

When he is not directing passionate actors for hours after school or guiding older theater students through the production of their own plays, Towers can be found sitting at a desk in his home office, his headphones blaring and his mind turned on. Focusing primarily on ten-minute plays, Towers is also a playwright, who has won many awards and has had plays recognized across four continents.

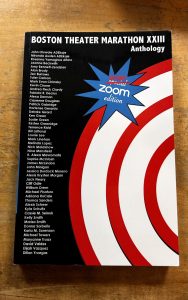

His plays have caught the attention of many theatre companies across the world. Towers’ play Pole Position was produced in Sydney, Australia and named a Short+Sweet Finalist in Hollywood, California; Essex, United Kingdom; Perth, Australia; Dubai, United Arab Emirates; and Illawarra, Australia. Another one of his plays, Molting, has earned notoriety with stage, film, Zoom, and radio productions.

“When I wrote Molting, I didn’t finish it and [consider it to be] the best play I’ve ever written. […] I thought it was good, I thought it was meaningful, I thought it was sweet, but I didn’t really, in the moment, think ‘this is going to be the one that puts me over the top,’ and it has been my most successful play,” Towers said.

Molting is about a young girl and her father who are sitting at a table sharing a lobster dinner. It covers themes such as morality and the end of a marriage, but amongst its seriousness, audiences can still find comedy woven throughout the discussion. The play was featured as one of the top 30 plays in one of the largest and most prestigious short play festivals in the country, and has gotten productions in New York.

With Molting being one such example, Towers often explores the same interesting subjects in his plays: religion, the natural world, marriage, and the dynamic relationships between teachers and their students. Some can be light-hearted and animal-centric, inspired by Towers’ love for his wife and for animals. They mostly follow marine animals, such as sand dollars, sea turtles, and whales. Other plays can be heartbreaking, such as one titled Room 221, about school violence where a student stays behind with their teacher when all the other students have fled.

“Even though some of [my plays] are dark and sad, they come from what I would consider beautiful places,” Towers said. [Room 221] came from an Alice drill. We were standing at the door, waiting for the banging on the door, because we were told [we would experience some,] given the script that was slid under the door. [A] student I didn’t really even know leaned over and whispered into my ear, ‘I got you, Mr. Towers.’ And that to me, was a beautiful moment.”

Although Towers has achieved widespread success with his plays, the path to his achievements was not easy. The first step in the process of getting a play published in an anthology or produced in a festival involves doing research to find out what theaters align with Towers or his work. Then, Towers must submit his work to the theaters or anthropologies, which can be a lengthy process that often ends in rejection, a lack of response, or an acceptance letter a year later.

According to Towers, when he took a sabbatical to write between 2021 and 2022, there were some weeks that he spent 40 hours alone just submitting his work. In a separate year, he was able to get 35 acceptances for his plays, but those 35 accepted plays came from a group of 450 submissions. To Towers, being a playwright involves having the ability to put oneself out there, even though it can lead to four submissions and one rejection every day. He also believes that playwriting takes a lot of passion as it is not a job usually associated with wealth.

“There’s not a whole lot of money to be made, especially in short plays. You don’t write to make money. Maybe at some point, you get to a point where people recognize your name,” Towers said. “We at [WATA] have to make every dollar that we spend. That’s the theater industry, you make what you spend. You spend what you make, and you keep your head above water. That’s professional theater, that’s university theater, that’s educational theater. You’ve got to do [theater] for the love and because it feeds your soul, and [because] it’s very rewarding to see someone else’s interest in your work.”

Towers’ passion for theatre originated during his time in high school at WA. He received his Master of Fine Arts in Playwriting from Boston University under the direction of Kate Snodgrass, Melinda Lopez, and Ronan Noone. After finishing his college education, Towers returned to WA where he taught English classes along with a few theater classes once he founded WATA. But after the program picked up speed, he switched to only teaching theater classes, with one of them being Playlab Honors, in which one of the objectives is to write, direct, design and produce an original work.

“The truth is, [Towers] teaches us to write real stories, to write plays about everyday conversations and add [yourself] into it,” Playlab senior Ruby Davis said. “He taught me how to write a 10-minute play and thanks to his help, [I] along with one other classmate, and [Towers] himself are having our plays produced in the Boston Playwright Marathon this spring. In the end, I have him to thank for everything I know now.”

Ultimately, Towers has been writing plays for almost his entire life, and, according to Towers, he will continue to write plays for the rest of his life. Although he has dipped his toe into all that the theater world has to offer, from set design to acting to directing, for Towers, playwriting will always hold a special place in his heart.

“I like to move people, and that’s what we artists strive to do, whether it’s a play that we are directing, a play that we are acting in, a painting that we hang on the wall, music that we record, or plays that we write. The plays that you write [are] probably the [rawest] form, and therefore it is the most rewarding when they work,” Towers said. “There is nothing like being a playwright when your play is being produced [because] it hurts. You know it’s hard to watch and that you’re exposed out there. But it’s also extraordinarily rewarding. So I’d say for me, now that at this stage of my life, I’m ready to focus my energies [on] being a writer.”