Every year, we take on new challenges. The goal is for students to prepare themselves, whether that be for their future or next year’s courses. However, these preparations must suit the future we look towards. This future, while still unclear, now shifts with the emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) on an educational level.

Whether it is due to newly accessible plagiarism through AI software or just a general preference of some teachers, there has been a notable shift to in-class essay writing over the past few years. And while this style proves to provide many benefits to students, it takes on an entirely different skill set that should start being practiced in younger grades to prepare students for the changes at the high school level.

The concept of in-class essays have been around long before AI and even the pandemic, and as such they continue to highlight a different student skill set. In-class essays, as opposed to take-home writing assignments, display time management and identify the workings of a student’s mind that can analyze and develop thoughts quickly.

Jeanette Decelles-Zwernemen, founder of an educational resources nonprofit Cana Academy, describes the in-class essay’s purpose as work designed “to put the students in the position of thinking through a problem with discipline, independence, and efficiency.”

Additionally, these projects are often graded with leniency on grammatical errors and eliminate the distractions and procrastination that many students feel at home.

Yet, despite these benefits in the improvement of education, there is still a large disdain against in-class essays amongst students. This disdain originates from an anxiety caused by time restraints.

“I would definitely procrastinate [take-home papers], but I feel like I focus better at home. So I [would want to] do the [essays] at home, because I work better at home,” sophomore Aanya Krishnamurthy said.

When students are put into situations where they know they have to leave the classroom with a paper written, it can often cause them to freeze up and have difficulty producing a full five-paragraph essay. These issues can be magnified for students who already struggle with anxiety and slow processing speed.

Additionally, many students transfer to the Westford school district simply for its highly regarded academic qualifications. Now ranking 13th out of all Massachusetts school districts by community and educational database Niche, it is possible that many students who move to the area for these resources received different degrees of lessons from their previous locations.

“I moved here in eighth grade […] My first time writing an essay was in eighth grade. So […] of course I learned stuff at my old school, but at the same time, [WA students] learn different things, so it was hard for me to adapt at first,” sophomore Amira Mazouzi said.

In these cases, working in more time to focus on a skillset more and more prevalent at WA will be beneficial to both newcoming and prestanding portions of the student body.

Still, in-class essays are not a new concept. Perhaps years ago students could manage a few of these style exams interspersed with take-home essays, but there is now a clear shift to one side of the spectrum.

The issue here is that there are very few ways to limit the level of in-class writing now. AI, as the world knows, is not something easily eradicated. And while some teachers at WA utilize certain assets the digital intelligence provides, others are skeptical of the authenticity of plagiarism detectors.

In-class essays are also already guaranteed in many WPS administered standardized testing, such as midterms, finals, MCAS, and AP exams. AP Literature & Composition teacher Kimberly Hart also states that her class has switched completely to in-class writing.

“I think anecdotally, I’ve heard a lot of colleagues mention seeing AI generated stuff show up in student work, and that is causing them to think about whether or not they just want to move to in-class writing,” Hart said. “Part of the consideration is also when we move from the six-drop-one to the five-drop-two [class scheduling], we lost something like 20 to 30 class days of teaching. […] So we’re still trying to navigate what the cost-benefit analysis is of what we do in class.”

And while some may argue that it is not a prevalent problem at WA, the conditions of “use of AI based language generators” has since been added to the school handbook, stating, “any act of plagiarism, including the use of AI, whether intentional or unintentional, may be subject to Westford Academy’s academic integrity policies.”

So like any other change, we must work to adjust and live with the possibility of AI. Writing and analysis, however, are not skills you can teach with flashcards and a quizlet. Rather, they must be practiced.

“Good writing is a marriage of understanding the content and the craft of writing. And both of those things are challenges in and of themselves and learn skills,” Hart said.

Granted, younger students learn the basics for their essays. They learn the structure and placement of content within a standard five paragraph essay, then practice it through at-home papers. These skills, while incredibly crucial, do not cover all the aspects required for in-class writing. Specifically, it does not develop quicker processing skills.

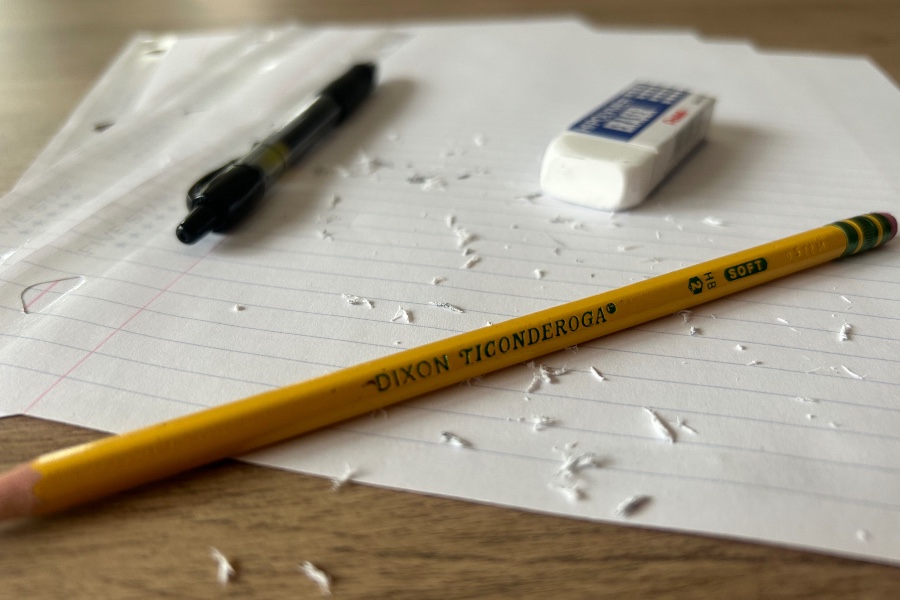

And so, in order to simultaneously prepare for and reduce the dislike of in-class essays as these changes in assignments are being made, more practice needs to be administered at a younger level. This could be as simple as giving more chances to write by hand, even ungraded, in a strictly class setting to develop these skills.

This will adjust the students to this writing style at a younger age, even just at the end of middle school, and allow them to understand how to prepare for both types of writing.