Opinion: ChatGPT highlights the importance of adapting to AI

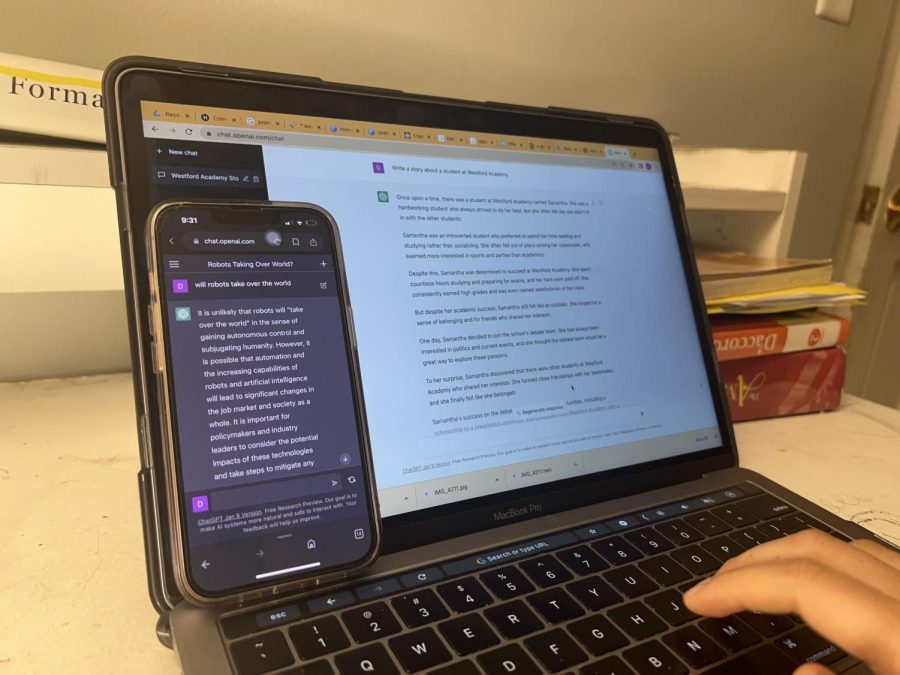

With the rapid evolution of technology, this image depicts the various capabilities of the new ChatGPT tool, which can be used on iPhones and computers.

January 21, 2023

30 seconds. That’s all it takes for Chat GPT to write articulate essays, thought poetry, song lyrics, give advice to life’s most pressing challenges, and even solve long-winded math problems. This is the product of OpenAI’s newest technology, released on Nov. 30: a conversational artificial intelligence (AI) that can respond to virtually any request.

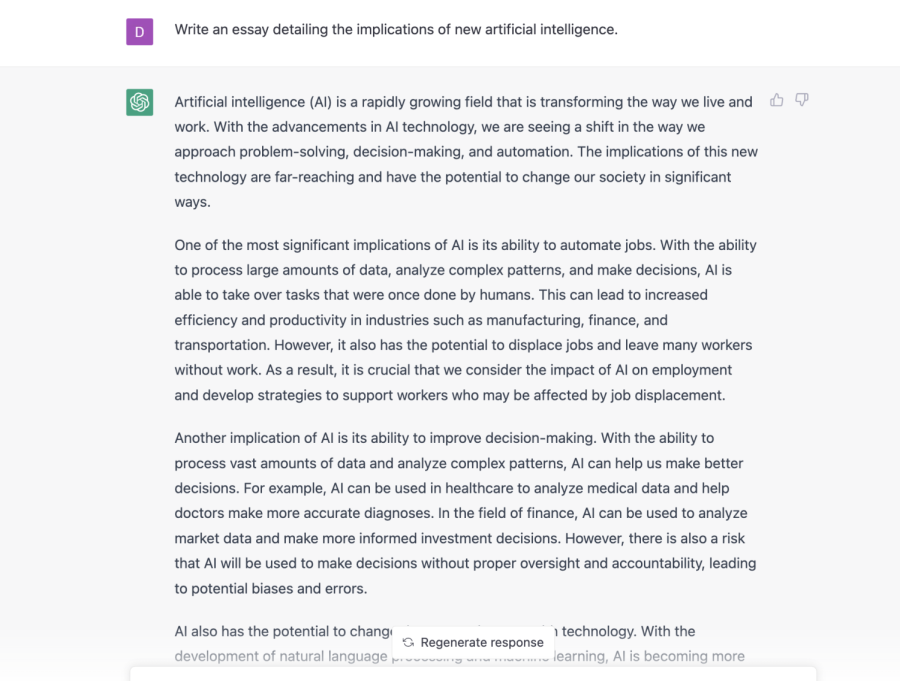

As shown below, Chat GPT is unique in its stunning ability to give human-like responses to a variety of prompts and questions. Unlike most other chatbots, CHAtGPT is trained to generate creative, personalized responses that can remember and refine its response based on feedback and even mimic writing styles. Because the data comes from a wide database of all sources on the internet, the bot is able to produce original writing that has yet to be detected by plagiarism detectors.

When most people first try out the chat box, their initial response is awe, followed by the inevitable fear: is this the end of writing as we know it? And, for teachers and those in education, there is a growing concern for the many ways in which such technology can be misused by students to plagiarize, posing a new question: how do we utilize these new technologies to enhance student learning, rather than hinder it?

Personally, I believe that the rise of tools like ChatGPT should be seen as an opportunity to adapt and enhance our curriculum model. For one, with the rapid pace of technological development, it will soon become near-impossible for educators to suppress and track down the widespread misuse of AI. Instead of attempting to slow down this inevitable development solely with limitations and futile bans, it will become necessary to both understand and incorporate AI into the way we learn.

In some ways, AI has already made a vital impact on our writing process over just the last decade. Many of us cannot imagine writing without a spell checker or Grammarly by our sides, and most students prefer to type with a phone or Chromebook on hand, rather than paper. With the COVID-19 pandemic, many of these adjustments in education have been accelerated, with students and teachers forced to adapt their lessons to a virtual classroom.

Although it was assumed that creative skills such as writing are uniquely human tasks, it is clear with ChatGPT that this will not always be the case. Busy work, or writing that is simply assigned to keep students working rather than learning, will lose even more value as students resort to technology to find answers. Instead, the focus should be held on process-based learning that places an emphasis on brainstorming and critical thinking.

For example, writing an essay is more than just the shiny packet of papers that we turn in at the end. It is about the process of researching a topic, generating a thesis, critically thinking about reasoning, finding a way to express it, as well as strengthening our skill of writing,

In order to bring this idea home for students, the curriculum should be tailored towards the learning process, not the end product. Rather than putting pressure on one final grade, more emphasis should be put on brainstorming and first drafts. This would not only ensure the originality of student work and ideas but also ensure that a student is working efficiently and improving.

According to English Curriculum Coordinator Janet Keirstead, this is something that the English Department has been working towards in the last few years.

“I think the difficulty is, how do we help students see why we’re doing what we’re doing, and get them to buy into why it isn’t a meaningful and important task,” Keirstead said. “And that’s really the big downside that I’ve seen. It’s not necessarily an increase in cheating because we’ve always had cheating, but it’s harder for students to build up resiliency and an understanding that some things take longer than others.”

As for ChatGPT, Keirsted is looking to find ways to both adapt and evolve with the technology. Not only does the English Department hold students to a higher standard than most of the formulaic responses created by the chatbox, but also typically assigns in-class writing.

“I think it fascinates me because I’m not one of those people who’s like ‘no technology.’ It is not the root of all evil,” Keirstead said. “It’s a question in part of how do we help students understand when it’s appropriate when it’s not?”

But is AI all bad? In a conversation with library technician Stephanie Gosselin, I found that many educators have looked into ways of incorporating AI into classroom lessons. For example, students can critique AI written responses, while teachers can use the tool to generate more personalized and unique prompts. In addition, when I experimented with the chatbox, I was surprised to see that it was excellent at giving edits and proofreading, with suggestions similar to what my teachers or peers would give me.

As the chat box continuously improves, it will ultimately be necessary to work alongside technology, rather than against it – especially in the classroom. Admittedly, although there are ways that technology will forever change education, it also brings about thousands of possibilities. From new learning processes to improved classroom prompts, we are yet to find the new way of life that will emerge when we embrace change.