Woman of the Month: Savior of the Huddled Masses

https://cdn4.picryl.com/photo/1935/01/01/frances-perkins-center-4-1024.jpg

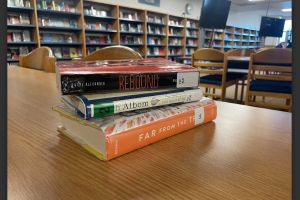

As Secretary of Labor, Frances Perkins worked with numerous influential politicians including President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

December 1, 2020

Dedicating her life to social reform, and as the first female Cabinet member, Frances Perkins was a revolutionary.

Born in Boston, raised in Worcester, and educated at Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley, Massachusetts, Perkins spent her formative years in New England. Perkins pursued physics and chemistry at Mount Holyoke, unusual subjects for a woman of her time. While at Mount Holyoke, Perkins was inspired by Florence Kelly, then secretary of the National Consumers League. Inspired by Kelly’s advocacy for the eradication of sweatshops and child labor, Perkins dedicated her life to serving the underserved, particularly immigrants, children, and women.

Three years after her graduation, Perkins joined the Hull House, a soon-to-be-famous settlement house in Chicago, Illinois. Having grown up in a middle-class family, Perkins witnessed first hand the effects of poverty, lack of education, and lack of social resources on low-income, urban communities. Despite being able to aid a small number of the impoverished through direct services, Perkins realized that “until certain laws were changed or created in the United States, no real change in the circumstances of the poor would be possible” (Perkins, Frances [Gale Encyclopedia of U.S. Economic History]).

In 1907, Perkins moved to Philadelphia to attend the University of Pennsylvania’s business school. While there, she became a social worker, lobbying against the exploitation of immigrant women and African Americans who had relocated to the North. Two years later, she relocated to New York City, and, in 1910, finished her master’s degree in economics and sociology at Columbia University. Upon graduation, Perkins became the New York City Consumers League’s executive secretary. Additionally, Perkins took a leadership role in the burgeoning suffrage movement centered in New York City.

Working for the Consumers League, Perkins sought to improve business sanitary conditions, formulate fire-safety legislation, and pass “a 54-hour-week maximum labor law that would limit work hours of women and children under the age of eighteen” (Perkins, Frances [Gale Encyclopedia of U.S. Economic History]).

On March 25, 1911, a raging fire broke out at the Triangle Shirtwaist Company. Perkins watched in horror as people trapped in the building leapt or fell to their deaths. When it was all over, 147 people had perished (Perkins, Frances [West’s Encyclopedia of American Law]). Perkins’s demands for legislative action following the fire led to the establishment of the Factory Investigation Commission. “Based on the commission’s findings, New York enacted more than thirty laws protecting industrial workers” (Perkins, Frances [Encyclopedia of the Great Depression]).

In 1919, Assembly leader Alfred Smith became Governor of New York. Smith appointed Perkins to New York’s Industrial Commission. When Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) became New York’s governor in 1929, he promoted her to industrial commissioner. As commissioner, Perkins promoted federal aid and unemployment insurance for the jobless.

When FDR won the presidency in 1933, he appointed Perkins Secretary of Labor, making her “the first female member of a presidential cabinet in U.S. history” (Perkins, Frances [Gale Encyclopedia of U.S. Economic History]). Perkins was the only cabinet member to serve for the duration of FDR’s four terms (Perkins, Frances [West’s Encyclopedia of American Law]). Despite the outrage at the appointment of a woman and the immense pressure Perkins felt, during the Great Depression, she transformed the Department of Labor and repaired the reputation of the Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization, an organization then regarded as one prone to illegal deportations and bribery.

As FDR’s Secretary of Labor, Perkins was instrumental in the development of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, the Civilian Conservation Corps, and the Public Works Administration, three key components of the New Deal. Furthermore, she tasked the Labor Department’s lawyers with drafting a child labor-banning, maximum hour, and minimum wage bill. In 1938, the Fair Labor Standards Act, a watered-down version of the bill Perkins fought for, passed Congress and was signed into law.

In June 1934, Perkins was appointed as the chairperson of FDR’s newly created Committee on Economic Security. With the aid of numerous federal and state officials and experts, Perkins successfully delivered a recommendation that formed the basis of the 1935 Social Security Act. “Disappointed by the law’s exclusion of farm, domestic, and some other workers, [Perkins] fought for the rest of her life to extend social security to everyone” (Perkins, Frances [Encyclopedia of the Great Depression]).

Her continued support of organized labor and compassion for the unemployed earned her a reputation as a communist sympathizer, despite her clear distrust of the Communist Party. In 1938, the House Un-American Activities Committee accused her of being a communist and attempted to impeach her, nearly costing her her post as Secretary of Labor. The attempt was unsuccessful and Perkins remained Secretary of Labor until stepping down in 1945. She remained a valuable asset to the government, working as a member of President Harry S. Truman’s Civil Service Commission until her retirement in 1953.

Until her death in 1965, Perkins devoted her life to social reform. She lectured at many colleges and became a visiting professor at Cornell’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations.

Today, millions of Americans live better and safer thanks to Frances Perkins. “Every man and woman in America who works at a living wage, under safe conditions, for reasonable hours, or who is protected by unemployment insurance or social security, is her debtor” — Secretary of Labor Willard Wirtz (1965) (Perkins, Frances [Encyclopedia of the Great Depression]).

Frances Perkins devoted her entire life to bettering the lives of others. Whether they were U.S. citizens or immigrants, Perkins was determined to establish legislation that would protect the people living in the United States. From the moment she was introduced to Florence Kelley, Perkins had clear goals for her life. Throughout her time as the commissioner of New York’s Industrial Commission and as U.S. Secretary of Labor, Perkins focused on those goals. She set out to change the circumstances of the poor by altering and enacting certain laws in the United States. With the numerous acts she helped create, including the Fair Labor Standards Act and the 1935 Social Security Act, Frances Perkins easily crushed her goals.