All the Bright Places represents “all the colors in one”—a murky brown

Courtesy of a Netflix press release

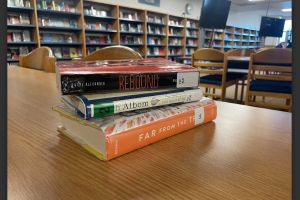

Violet and Finch (Fanning and Smith) share an intimate moment with each other.

March 15, 2020

In past years, many TV shows have attempted to depict teenagers’ struggles with mental illness. Whether it be “13 Reasons Why” in 2017 or more recent shows such as “This is Us,” the accuracy of these portrayals is always being debated. Some claim that mental illness is forever romanticized by the media, while others say that certain shows have helped people come to terms with their own mental health issues.

Based on Jennifer Niven’s 2015 novel of the same name, All the Bright Places, a film that premiered on Netflix on February 28, attempts to tackle the same issue. Violet Markey (Elle Fanning), grieving the loss of her sister Eleanor, finds herself standing on the ledge above a river during the day that would have been Eleanor’s nineteenth birthday. On his morning run, Theodore Finch (Justice Smith), the school “freak,” stops her from going any further.

Together, Violet and Finch tackle a school project about the wonders of Indiana, all while discovering the intricacies of their newfound friendship. Through Finch’s encouragement, Violet learns what it means to truly live again, while Finch finds happiness through Violet, in spite of his own mental health issues.

In the end, although the movie attempts to spin a poignant tale about teenage romance and overcoming mental illness, All the Bright Places falls short of expectations.

The movie’s innumerable issues can be traced all the way back to the stylistic choices of the script. Niven’s novel is told in parts, alternating between Finch and Violet’s perspectives. Each part reads like a diary entry, revealing the character’s inner thoughts, emotions, and secrets.

However, despite the movie’s attempts to mirror the same format, it lacks all of the depth that its written counterpart was able to achieve. Every scene in the first half of the movie is clipped and serves simply as a means to force the two main characters together as quickly as possible. Rather than creating nuanced, sophisticated personalities, each character is merely an archetype of a typical character in a teen fiction novel.

Therefore, once Violet and Finch are together, the lack of emotional connection with any of the individual characters and the horrendous pacing makes it hard for the viewers to feel anything at all. Violet is furiously refusing Finch’s attempts at friendship in one scene and the two are making out in the next. There is no logical development of a relationship between the two. Violet and Finch are merely puppets forced to play “house” by the screenwriters.

On top of the script, the two main leads pose problems for the movie—there is absolutely zero chemistry between them for the first fifty minutes. Although the artsy musical montages of Violet and Finch spending time together tries to patch up the holes in their acting, nothing can make up for the awkward small talk and the nonexistent bond between Fanning and Smith.

Additionally, the dialogue does nothing to ameliorate the movie’s problems. It simply encompasses all the worst clichés of teen fiction. Violet and Finch deliver cheesy pickup lines and attempt to be clever by reciting Virginia Woolf quotes to one another. Although the screenwriters attempt to use these lines as a way to make up for their mutual lack of interest and otherwise dull conversations, they only make the actors’ performances worse.

In one scene, Finch gives Violet the nickname “Ultraviolet,” and tries to be cute by telling her that she is “all the colors in one, at full brightness.” Nausea is not enough to describe the migraine-inducing feeling of watching that repulsive screenwriting unfold.

In spite of all the flaws in the first half, the second half’s narrative about mental health does a better job compared to predecessors. However, there are so many intricacies to his illness that could have been explored much further. Nothing is clearly defined—Finch refuses to stick a label on his mental health issues, for example—which means that the creators of this movie are not able to glamorize mental illness as much, but the message being sent to viewers also isn’t as clear.

Additionally, unlike “13 Reasons Why,” the premise of the movie is not solely centered around suicide. “13 Reasons Why” starts in the aftermath of suicide, and may have suggested to some viewers that there is always someone to blame for someone else’s suicide. All the Bright Places explores the more triggering aspects of mental illness later on in the film and chooses mainly to focus on the relationship between Violet and Finch. Although the media’s depiction of mental illness still needs work, All the Bright Places is definitely an improvement from previous attempts.

Ultimately, however, the first half of the movie is best watched on mute, the second half’s narrative about mental health is left underdeveloped, and the entire movie lacks depth. Perhaps the movie would have been enjoyable if the plot had other goals aside from narrating love and mental illness. However, because the movie does a lousy job of delivering on both components of the plot, even the stellar production quality cannot fix the incomprehensible mess that is this movie.

2.5/10