By Craig Brinkerhoff

By Craig Brinkerhoff

Copy Editor

This piece is a part of a series exploring how new technology will be changing how teaching is approached at WA. For the other pieces, see How WA Does Technology.

Obviously, technological innovation is not slowing down anytime soon. Two years down the road, my phone is going to be considered bulky and outdated, and then two years after that, phones will not even be the same shape as the phones we know of now.

This talk of technological innovation finds itself interspersed into discussions on many social normalities, such as sports or business or school. In the realm of sports, people are finding amazing ways to document how the body acts during exercise and how to best prepare athletes for peak conditioning.

Now, the problem with attaching this much technology to sports is that it loses the essence of what it is: sport. When we see high-profile cyclists hooked up to CO2 respirators or a baseball player using programs for pitch accuracy and predictions and whatnot, it shows the problem with this kind of approach to sports. The tubes and the wires and the sheer amount of data get in the way of actual training and progress.

Furthermore, the above argument does not even get into funding. Massive amounts of money are being dumped into these technological programs to supposedly help the athlete, but all that happens is the owners hand over more cash than before and the athlete gets minimal benefits.

Now take a step back. The above ideas directly correlate to the recent surge of technology in the classroom and, like sports technology, there are only minimal benefits. Yes, Antonelli’s new idea for going one-to-one sounds great in theory, and the idea is absolutely solid in its goals, but it will yield few benefits.

Those benefits would include a more visual approach to things, multiple viewpoints on issues, more room for creative expression; the list goes on and on. Yet, for the amount of money the town is going to have to cough up to initiate the program, there will be too many students using “tablet-time” to mean “play time,” and those benefits will never come to the surface. Antonelli said it himself.

“Now it’s not perfect, because I don’t want to just see kids staring at iPads all class. We do enough of that … I don’t want it just to become a unilateral approach of just looking at this machine and not communicating with adults,” he says.

There is always room for improvement. Building upon the networks we have and the practices we have makes sense (the WiFi infrastructure really needs to be redone), but perhaps there is another way that will not distract from learning quite as much. If every student has their face buried into a screen, they can see things more visually, but they will also discover that iPads can access Facebook and Twitter and soon enough less progress is to be made in the classroom. It is a fine line that administration will have to walk.

Next, we have to take into account the penalties of too much screen time. Aside from the physical detriments, Public Health England has even come out and said that too much can lead to higher levels of depression, anxiety, and emotional distress. We spend enough time sitting in chairs at school and at work, how could placidly staring at a screen for even more hours be good for you?

Finally, we have to look at funding. K-12 Director of Digital Learning Julie Elkan was blunt with me that funding is always a problem, and that at least grants are plentiful. As with the sports analogy, a one-to-one program is simply going to lead to spending tons on something with such tiny benefits as seeing things visually that we can already see on the InFocus projectors we have.

“To fund a whole one-to-one initiative is going to take more than grants,” Elkan says.

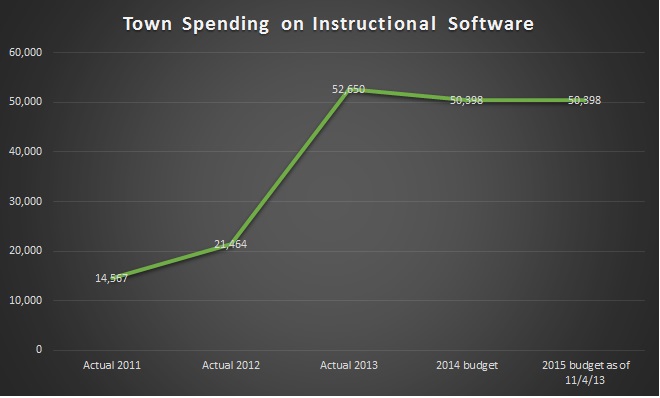

In relation to software, of which a similar pattern is developing, below is a graph charting how spending on instructional software within the town’s school budget has jumped considerably as the push for more technology begins.

Do not get me wrong, I would love to see more technology in the schools. It provides a visual and auditory way to see information differently, to help with those difficult concepts. The problem, though, is when we take these ideas too far and want to initiate programs for less return than we anticipate.

Just like the runners with a twelve-function watch that can also work up to four hundred feet underwater, a one-to-one program seems like a fad, and that if instated, would lose its shine and glimmer pretty soon. And we’d still have to pay for that novelty for years to come.