Budget breakdown IV: An unsustainable present, a tentative future

April 18, 2019

In the previous installments of this budget series (I, II, III) we discussed the how and the why of the school’s budget deficit that caught public attention this year but has in actuality been persisting for multiple years. Now, we look to the future: can this situation continue, and if not, what needs to change?

An unsustainable present

Superintendent of Schools Everett Olsen calls fiscal years 2019 and 2020 the most difficult he has encountered in his career as superintendent. In both years, he has had to make over a million dollars of cuts to the school budget in order to meet the town’s budget allocation. Though the budget continues to increase year to year, costs are rising far more.

Tax rates are checked by Proposition 2 1/2, while according to Olsen 90 percent of the school budget is inflexible due to fixed contracts and salaries. As costs continue to rise at a rate with which the 2.5 percent annual tax increase cannot keep pace, one of these two factors will be compromised.

Until this point, invisible and creative cuts as well as the low teacher salaries have allowed Westford to maintain a high-quality school system at a low cost, says School Committee member Gloria Miller.

If the school budget continues to face smaller budget increases, Miller notes that impacts on class sizes may begin to affect the school system’s educational quality. Since most of the school budget cannot be altered, should more cuts become necessary, teachers and teacher assistants may be removed or not hired despite growth, leading to an increase in class sizes.

Selectman Mark Kost explains that the point at which class sizes transform from acceptable to detrimental is unclear, and as such it is difficult to mark at what point increasing class sizes become an issues.

“I don’t know if there’s a huge difference with a 20:1 vs. a 21:1 vs. a 22:1 ratio […] I don’t know where the fallout is,” he said.

Miller asserts that Westford’s low class sizes are a hallmark of the Westford Public Schools, and that small changes add up.

“Westford has found out that by keeping those [student-teacher ratio] numbers low, especially at the lower grades, there really is a return on investment there,” she said.

Miller also emphasizes that with the current budget pressures, simply maintaining the school system is a difficult endeavor, and this state of “treading water” makes it impossible to innovate and expand in a changing world. For example, the proposition to change the school start times based on research that starting school later greatly benefits students was slashed due to its impact on an already-strained budget.

In addition, with Westford experiencing a population boom unseen since the 1980s, property values continue to rise. Finance Committee Chair Gerald Koehr described the migration into Westford as circular, with the school system’s excellence prompting migration which in turn drives up both the school budget and property values, leading to Westford’s property values being as high as they are currently.

According to Principal Assessor Jean-Paul Plouffe, this, too, is an unsustainable situation. Median entry-level property sales, he says, are crossing $400,000, and though a market still exists for such prices in Westford, this may not remain true.

“In terms of real estate value, people are paying for properties right now. I expect that bubble’s going to burst. And what it does, and how bad that impact will be, we really don’t know,” he said.

It is not just the school system which is in this tenuous situation; all of the town departments face cuts and less-than-optimal employment numbers. For example, the fire department could not hire up to its recommended number of employees for Westford’s population despite its budget increasing significantly.

“All the departments feel the pinch,” said Kost, who does not foresee the budget tightness being alleviated if cost and revenue conditions continue.

However, some town officials maintain a positive outlook. Finance Director Dan O’Donnell asserts that there are still more ways to divide the tax revenues in such ways that continue to fund all the departments.

“Changes aren’t always bad. […] we’re always looking towards stretching taxpayer money and trying to find efficiencies,” he said.

“It’s difficult, but as usual, I’m optimistic that we will figure out a way,” said Town Manager Jodi Ross.

A tentative future

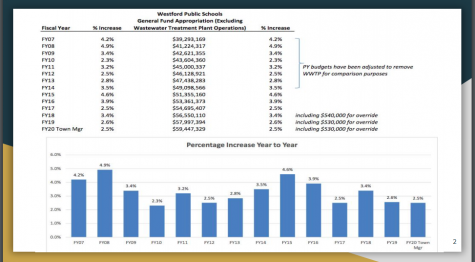

In its annual budget worksheet, the town government projects costs and revenues for the next three years. In the projection, the school budget allocation continues to increase by 2.5 percent every year, though Olsen’s previous budget increase requests (3.3 percent being the most recent) and the variable nature of budget allocations in the past (see graph below) indicate that this may not be the case.

Tax revenue increases, however, seem to be looking up with the population influx, and could alleviate some of the budget pressures in coming years. Revenues are projected to increase 3.6 percent for FY21.

“We’ll be in good shape for next year, so I’m not too concerned at the moment,” said O’Donnell.

Major issues affecting the town, though, will not disappear in the long term despite revenue fluctuations from year to year. Part II of this series discussed ways in which Westford’s tax situation — a high percentage of children who not pay taxes coupled with a fairly low property tax and a lack of regular tax overrides — contributes to the town’s budget crunch. Part III broke down the state funding formula’s detrimental impacts on school districts across Massachusetts.

In short, one of these two factors — the tax situation in Westford or the state funding formula — must change for this budget issue to be resolved in the long term.

The solutions to the tax issue lie either in an increase in the state limit on property tax or Westford citizens passing more frequent tax overrides. Koehr proposes that the town may have to dip into budget reserves to support possible new teachers or buses due to enrollment increases next year, but could simultaneously plan an override for FY21. That way, the town would add significant revenues to its operating budget.

“People’s taxes will go up, that’s the only solution, or maybe we can convince the state,” Koehr said.

Olsen also believes raised taxes may be needed to fully fund the school system in the near future.

“Do I think that down the road — and I would say for all town departments, not only the school system — do I think perhaps we’re approaching the point where an override might be necessary? I do think that,” Olsen said.

In the way of state aid, there are movements occuring in the state legislature to revamp the Chapter 70 formula, decades having passed since its instatement. Though the last attempt to reform state aid failed last year due to disagreements within the state government, another attempt is now on the table.

The Promise Act, spurred by the Fund our Future coalition of education activists, is going through the current legislative session. Filed by State senators and representatives from Boston, Holyoke, and Worcester, the Promise Act would increase foundation budgets across the state for a total increase of over one billion dollars.

It accommodates the needs of low-income towns, English-language learning students, special education, and healthcare costs, the four issues School Committee Member Gloria Miller explains are most prevalent in the state funding formula. It also will increase the cost per pupil of all districts in Massachusetts and help balance losses some school districts are facing to charter schools, according to the Massachusetts Teacher Organization’s website.

If the Promise Act is passed, Westford will receive about one million dollars in additional state aid every year, says Miller. However, low-income districts would receive significantly more, which helps Westford’s student saturation issue and thereby reduces the school budget and the need for the above-discussed measures.

In conclusion

The program cuts and restructuring Westford Public Schools underwent in order to meet a $1.2 million deficit between its carry-forward and actual budgets has roots in multiple financial pressures in Westford. These cuts are only the first visible symptoms of a tightening budget, though in previous years similar deficits were closed through cost-cutting measures that did not directly impact students.

Westford is a middle-income town with a taxpayer base reluctant to pay higher taxes or pass frequent tax overrides, as is the case in Newton, Wellesley, and other high-income towns with strong school systems. At the same time, it is too affluent to receive significant state aid.

Additionally, property taxes are restricted to increasing 2.5% per year, which is not enough to keep up with rising general costs.

With its school system as the town’s hallmark, migration into the town is heavy and most new residents are families. As such, Westford has a high percentage of citizens under eighteen, who do not pay taxes but still require resources to go through the school system. In this sense, Westford is having difficulty supporting such a student-biased town, with so much pressure being placed on the schools due to the high number of students, yet little means to alleviate that pressure.

Especially as enrollment is projected to increase rapidly with the construction of over 700 new units over the next three years, supporting the students becomes an ever-growing concern. The FY20 budget, even with the program cuts and restructuring, does not cover the cost of hiring new teachers based on the projected new enrollment. When these hires become necessary, it is unclear what the source of that money will be, though the town government and the school system have a verbal agreement to work these issues out and support the new hires.

Finally, state aid to school systems has been falling short for years. The Chapter 70 Formula, instated in 1993, is long outdated. It fails to adequately compensate healthcare costs for school employees and special education costs, both of which have been rising faster

Though revenues may increase with the migration into Westford, this long-term budget tension is likely to persist. Increasing taxes in some form, either through another override or upping the 2.5 percent restriction, or changes to the state funding formula are the two most viable options.

Olsen asserts that the town government has provided strong support to the school system, but expresses the tensions that the Westford Public Schools currently face and the unsustainable nature of this situation looking forward:

“The difficulty of budgeting schools is that every human being is different […] there is such a variety in cognitive and social needs that it’s very difficult to be able to meet those needs with such constrained revenues,” Olsen said. “We’re going to be in trouble if [tax revenue] conditions continue.”