Budget breakdown II: Why Westford?

April 9, 2019

The Westford School Committee begins the search for a new Superintendent with Olsen’s retirement on the horizon.

In the first installment of this budget series, we looked at the immediate effects of the budget cuts and its lack of sustainability for the future. Now we look at how this budget deficit came about, the history of budget balancing in Westford, and where exactly the root of the problem is.

Westford runs a very lean school budget…

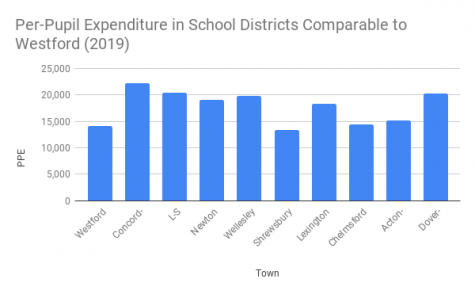

A low cost per pupil reflects still-low teacher salaries

Westford’ Per-Pupil Expenditure (PPE), or the the amount of money spent per pupil, is $14,131. This number is lower than the state average of $16,015, and schools that are academically comparable to Westford have much higher PPEs: Lexington spends $18,366, Concord-Carlisle spends $22,149, and Newton North and South spend $19,082.

These towns are wealthier than Westford, but even financially comparable schools tend to pay more than WPS, such as Bedford ($17,959), Sharon ($16,317), or Needham ($17,390).

The PPE is a good indicator of exactly how lean a budget a school system runs, because larger towns will have a larger budget but more students to compensate. Westford’s PPE indicates that the ratio between the budget and the number of students is fairly low, and that Westford operates on a tight budget.

However, the PPE has not impacted the quality of education in the Westford Public Schools, says School Committee member Gloria Miller. On the other hand, it reflects the low teacher salaries.

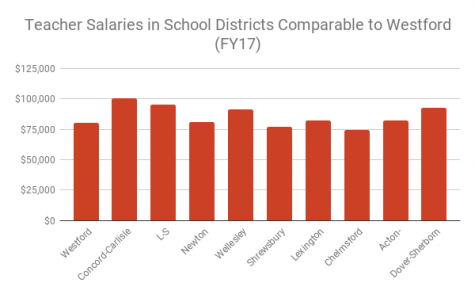

According to Superintendent Everett Olsen, salaries and fixed contracts account for about 90% of the school budget.

In FY17, Westford teachers were paid an average of $80,072 annually, which was prior to the tax override that added $540,000 to the total salary budget. Adding the override money over all 364 teachers in the district, the average salary goes up to $81,555.

Its retention rate, meaning the amount of teachers that stayed from year to year, was 88.40%, lower than all the comparison schools used in the graphs to the left and right.

The retention rate has not been re-calculated since the override.

Selectman Mark Kost explains that the teacher salaries were increased to meet the average of a calculated “market basket” of comparable schools.

Miller argues, though, that just because the teacher salaries are now average does not mean that change is no longer needed.

“Westford teachers aren’t average. Westford teachers should not just be making average salaries. […] We want to be able to maintain or even improve those numbers over time. But with the current budget crunch, how do we do that? And I worry about the long-term detrimental effect — if we aren’t able to pay our stuff adequately, how do we attract new staff and retain our current staff?” she said.

Olsen asserts that Westford is providing a quality education at an affordable price, referring to a ranking by NerdWallet that stated Westford had the most “bang for the buck” out of all the public high schools in Massachusetts.

“I think [the low PPE] is a compliment to the fact that whatever money we receive from the town, I think we spend wisely, that we try not to waste money, we try not to hire too many people,” he said. “We try to target services based on an analysis of student needs, both academic and social-emotional, so we try to run as lean as possible, but as effectively as possible.”

Town Manager Jodi Ross cites Westford Public Schools’ high rankings as proof that the town is not compromising on education with its lean budget.

“There’s a lot of ‘want to haves,’ but what can we actually afford? And we’re still coming out [as] the number three school system in the state, and so we’re doing remarkably well,” she said.

Kost commends the Westford Public Schools for its efficiency, but in the spirit of imitating the private sector, asserts that there is always more that can be done to slim the budget while maintaining a high-quality education.

Having worked in the private sector for 35 years, Kost stresses the importance of efficiency and constant restructuring that private-sector organizations have mastered in order to make profit. Though the public sector is more reluctant to do so, he says, it is essential that the town begins to to learn how to maximize efficiency.

“If [after doing something efficiently] you have the CEO of a company that tells you to be even more efficient and then you don’t continue that efficiency, you wouldn’t have a job anymore,” said Kost.

… so why the money crunch?

A town of children: Westford’s high student population hinders tax revenues

Kost noted that one of the aspects of Westford which most distinguished it from other comparable towns was its percentage of the population under 18.

According to the 2010 census, the Westford student population was 29.7%. Only districts like Lincoln-Sudbury eclipse Westford; Acton-Boxborough, Chelmsford, Bedford and several others have two to six percentage points less. Commercially-focused large towns like Newton are even lower, with Newton’s population standing at 21.6% students.

Westford is known primarily for its school system. As such, the in-migration to the town is heavily biased towards families with young children who then grow up in the district. More children means less taxpayers, leading to decreased revenues to pay for an ever-growing school system.

Not only does this high percentage decrease the taxpayer base, but it puts pressure on the town to support a vast school system with comparatively less money. According to Finance Committee Chair Gerald Koehr, Westford’s school budget is much larger than several comparable towns, but the number of students it supports with that budget is even greater.

“I think that’s the big thing people have got to understand. It’s like a circle, right. The town has good schools, it attracts more students, it drives up the property taxes, drives up the need for more money in the schools, and things like that,” he said.

Free cash is not viable for school investments

Free cash is a budget reserve that is saved for emergencies and paying for capital plans, or long-term investments. According to Finance Director Dan O’Donnell, budgets that have spare money or increases in revenue can be pooled to create the free cash segment of the municipal budget.

“We use [free cash] and actually count on that to pay for our capital plan,” says O’Donnell.

Budget reserves, which comprise five to ten percent of the operating budget according to O’Donnell, seem suited to close the budget deficit this year. However, utilizing free cash was not a viable option for helping balance the FY20 school budget, agree Ross, O’Donnell, and Olsen. Dipping into these reserves is a one-time solution, and continually using free cash limits the flexibility of the town to deal with a variety of types of budget years.

“You never really want a fixed budget. You want a flexible budget that can accommodate […] both the up and down years,” said Kost.

In previous years, free cash has been used to balance the budget. Between 2002 and 2015, between $2 million and $5 million have been used from free cash to meet budget needs. It has been one of Ross’ key accomplishments to consistently balance the budget without using free cash since 2015, O’Donnell says.

In addition, free cash is necessary for Westford to have strong capital and make sure it is financially stable, O’Donnell adds. As such, dipping into free cash to resolve this budget issue may trap the district into paying consistently out of free cash and decreasing flexibility and stability as in the past.

“I mean, if we use free cash this year, to help balance the budget, we’re going to have lower increases for all the budgets the following year. So it’s, it’s easier to to make the tough choices each year rather make the very difficult ones [later],” O’Donnell said.

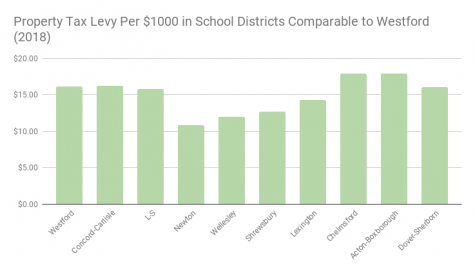

Low property taxes, commercial flat tax decrease town revenue

The components of the town budget are state aid, town revenue, and then taxes. The tax levy is determined by state aid and revenue.

Compared to neighboring towns, Westford has a relatively low property tax levy. Neighboring towns such as Chelmsford and Acton-Boxborough have tax levies between 17 and 18 dollars, while Westford is just over 16. However, the costs of properties have been increasing.

According to Westford’s Principal Assessor Jean Paul-Plouffe, there is no way to tell whether Westford will eventually be unable to develop any further. He described Westford as a bubble that keeps growing larger and more fragile.

“When I say we have this bubble, I expect is gonna pop. You know, depending on the economy and interest rates and everything else,” Plouffe said.

Residential tax lowers if commercial revenue increases, so Westford’s decrease in commercial revenue may lead to an increase in property tax as well.

In addition, Westford has a commercial flat tax, which means that businesses are taxed the same as residents, as opposed to bigger towns, which normally charge businesses more.

“Now with Cornerstone and places like that, maybe they [businesses] use more town services than a normal citizen would, you know, because the police are always up in Cornerstone dealing with accidents and things like that,” Koehr said.

Though the idea of removing the flat tax has been brought up in recent years, the Board of Selectmen has decided not to do so as a result of several years’ worth of decision-making, says Kost.

Having a higher commercial tax would not increase the revenue into the town significantly, due to the fact that only 15% of the town tax revenue is commercial while 85% is residential as well as the restrictions set by Proposition 2 ½ — taxes can only increase by 2.5% each year.

Though a higher commercial tax would make property taxes go down, as is the case in towns like Newton and Lexington, the total tax revenue still remains constant. The Board of Selectmen has therefore decided to maintain a flat tax commercially and residentially.

“It really doesn’t increase your taxes into the town, because you’re restricted by 2 ½. […] all they’re really doing is picking up a bigger share [of the taxes], so the residential will go down and the commercial will go up,” said Koehr.

Opinions are conflicted on the scope of business growth along Routes 40 and 110, with some members of town government asserting that there is room for building while others believe those roads are at capacity. In any case, the saturation is significant enough that great increases in revenue will be limited, especially considering the low percentage of the total tax revenue businesses comprise.

Middle-class status means less state aid, more reluctance for overrides

Municipal budgets have to be balanced every year, which means that towns cannot go into debt like the country can. Towns achieve this by balancing their costs with a combination of their tax revenues and state aid.

State aid is money that the state government gives to each town, depending on their wealth, which usually comes from its residential and commercial tax income. Towns like Westford with high property values get more revenue and therefore less state aid.

“Unfortunately, Westford is a fairly wealthy town, so we don’t get a big share of the pie like Lawrence would, or some towns that are less wealthy. The state tries to give to the more needy towns,” said Koehr.

However, Westford is far from the top percentile of wealth in Massachusetts. Miller stresses that while many citizens believe Westford is extremely affluent and are thus confused about why it has budget issues, Westford is actually in the 40th-60th wealth percentile.

“I think that people have the mistaken impression that Westford is a high-income community. Westford’s really a middle-income community […]” she said. “Westford gets caught up, I think, in this weird in-between. We’re not a low-income community that’s going to be receiving additional federal funds, but we’re also not a super high-income community like, say, Newton.”

Higher-earning towns have more leeway for spending on all departments, not just education, because their operating budget is higher. However, there is another significant process that towns like Newton can do with which Westford struggles: tax overrides.

By Proposition 2½, a Massachusetts statute passed in 1980, property taxes cannot be raised by more than 2.5% every year. This raise also does not keep up with the rate of increase of town costs.

If a vote is passed by citizens, though, the town can pass an override to raise the tax percentage. The last time the town passed an override was in FY17, in order to fund the increased teacher salaries, and was the only override passed in the last decade.

On the other hand, towns like Newton or Wellesley pass overrides regularly, says Miller, due to having a wealthier taxpayer base.

“Some communities just take [overrides] as a given. We’re not one of those communities. And I don’t think people want to become one of those communities. But I also think people don’t want the schools to be under-funded. So I think there’s a tension between wanting to adequately fund our schools, but not wanting to overtax, in particular, our seniors,” Miller said.

Ross explained that if the Board of Selectmen recommends an override, she will make that happen; however, as it stands, she is committed to making the budget balanced no matter what revenues may or may not arrive into the town.

“I continue to provide the best service that the town can provide within the confines of [proposition] two and a half. So I’m going to protect you, I’m going to have a fire station, I’m going to have a library for you, a senior center. We may not be able to introduce new programs, but we’re going to do the best we can within our budget,” Ross said.

Olsen believes Westford may be approaching a point where an override may be necessary, or that the state legislature reconsiders Proposition 2½.

“The indexing factor of Prop 2 ½ is so outdated that it’s really creating problems in town departments delivering services to the residents […] I’m hoping that at some point in time, the legislation will consider a different index, maybe Prop 3 ½,” he said.

Miller strongly supports the increasing of taxes through overrides for the long-term benefit of the town.

“I don’t know how Westford is going to be able to juggle this moving forward. Some people won’t like me saying it, but I think Westford may have to get comfortable with higher taxes, or more frequent overrides,” she said.

In the next installment of this budget series, read about the other major influencer of the current budget situation: state funding issues.

The nine comparison towns used in the graphs were selected by the Ghostwriter based on information from Superintendent Olsen. The first three are academically comparable towns and the second three are DART-comparable towns according to Olsen’s Budget Appendices. The last three were selected by the Ghostwriter as towns that are often compared to Westford by the public; Chelmsford for its proximity, Acton-Boxborough for its academic and demographic similarities, and Dover-Sherborn because it is the main comparison town for the Challenge Success program.