Advanced Placement advances stress

January 20, 2019

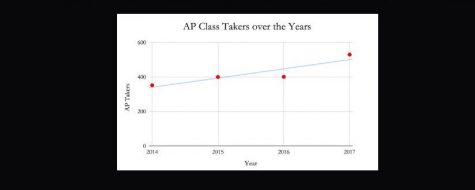

In 2017, 530 students at Westford Academy were in AP classes, according to the WA school profile. The number indicates a significant increase in the number of AP students, with 352 students taking APs in 2014, 400 in 2015, and 401 in 2016.

Whether it is to gain the approval of prestigious colleges or to simply advance one’s knowledge in a subject, the stress that comes with these advanced courses is inevitable. According to PrepScholar, Ivy League colleges expect students to tackle three to five APs per year in core subjects, while seven to twelve AP courses are what is considered necessary to stand out among others.

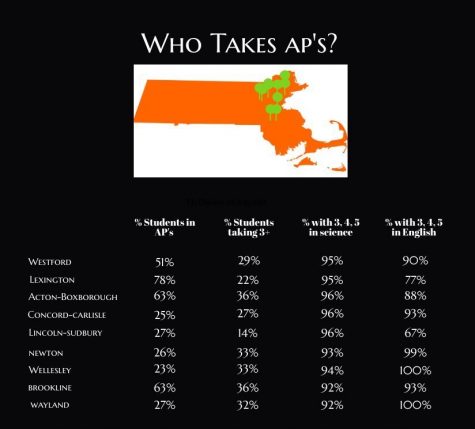

In schools all over Massachusetts, students face similar situations regarding their AP classes. In Westford Academy, 530 students take AP classes out of 1,715 total students, one-fourth of the school. Of these students, 29% take three or more APs. Compared to other high-achieving schools in the Boston area, Westford falls in the middle of the pack, with Lexington topping AP student numbers at 78%. Throughout districts, more students taking APs in total indicates there are less students taking three or more of them. Conversely, less students in AP courses in general means more are taking three or more APs.

However, AP classes are not necessarily taught at the same level in all districts. The issue, or boon, with WA’s AP classes are that many are taught at a higher standard than other schools. For example, the 3, 4, or 5 rate in classes such as AP French, AP Mandarin, and AP Calculus was 100% in the 2017-2018 school year. The average of students who score above a three for these classes on a national scale is 74%, 68%, and 56% respectively.

Overall, a substantial amount of students take the challenging AP courses that they know are harder than the conventional class. What are the various pressures and inspirations causing students to take several APs per year, and is the associated stress unreasonable or expected?

The AP Debate: Do You Bring Stress Upon Yourself?

In October, a student representative for Challenge Success posted on the Class of 2019 Facebook page asking what stresses students out. Over the next few days, hundreds of comments flooded the group.

Some criticized students taking difficult classes for bringing stress upon themselves, while others justified their class choices and argued that just because a course is challenging does not mean it should be unnecessarily stressful.

There a few key differences in mindset between the two ends of the argument. Those who feel that complaining about AP classes is unwarranted believe that students who take on more than they can handle are setting themselves up for failure and cannot blame teachers for any of their issues.

“I don’t mean to sound rude, but you signed up to take the class, you know what the expectations are, so you either can handle it, or you can’t. […] for people to complain that ‘oh, this is so much work,’ ‘oh, this is ridiculous, the teacher’s being unfair,’ it’s stupid, in my opinion,” said senior Amanda Mager.

On the other hand, some students argue that they take AP classes precisely because they can handle the work in terms of complexity, just not in volume.

Senior Tommy DeLuca enjoys being challenged, but does not believe that intellectual stimulation should come at the cost of physical and mental health. In this sense, there is a marked difference between a student’s intellectual and physical capabilities, and classes should try to strike a balance between the two.

DeLuca emphasizes that taking AP courses is much more complex from an AP student’s perspective.

“There’s just like different things, moving pieces, that aren’t recognized by non-AP students — which is totally understandable — but it gets to the point where it’s like, why are you inputting your knowledge into our lives?” he said.

Why Do Students Take Several APs?

Of course Advanced Placement courses are stressful. It’s in the name, after all — if they’re advanced, then why take so many?

It is hard to separate the reasoning behind taking several APs into a single pressure or cause. The belief in the importance of working to one’s full potential, the desire to meet a personal and peer standard, and the pressure to secure a successful future all impact different students in different ways.

Junior Isabella Xu, taking three APs, strives to take the maximum number of APs she can and chooses those she enjoys within that constraint. She does not consider the associated stress when making course selections, as she believes that her aspiration to work in the medical field requires her to get used to a backbreaking workload early on.

She enjoys working at a challenge and chooses difficult courses because she knows she would be disappointed in herself if she deliberately performed less than her best.

“I like to challenge myself to a point and see if I can handle something,” she said. “I feel like I’d be really bored if I took — since all my friends are taking APs I’d be like ‘oh, I want to try that out.'”

DeLuca follows a similar process, trying to stick to courses he enjoys but ultimately straying to some extent. However, for him, college acceptance plays a larger role.

“In a perfect world, I would say that it [taking 5 APs] was because I’m deeply interested in all the classes and I am for the most part, but I think a lot of it was because I have this pressure of college, that colleges won’t like me if I don’t take all these APs. And that’s not something that we can change, obviously,” he said.

DeLuca explains that the pressure to take multiple AP courses stems from, predictably, college. Selective colleges use numbers and difficulty of AP courses to determine an applicant’s competitiveness, and so the pressure is on to take a barrage of APs in order to meet the standards students are setting nationally.

According to the Princeton University website, “We consider it a promising sign when students challenge themselves with advanced courses in high school. We understand that not all secondary schools offer the same range of advanced courses, but our strongest candidates have taken full advantage of the academic opportunities available to them in their high schools […] Whenever you can, challenge yourself with the most rigorous courses possible, such as honors, Advanced Placement (AP) and dual-enrollment courses.”

Brown University echoes Princeton’s views on what a well-balanced student looks like, saying, “To assess preparedness, we review the depth and breadth of the academic learning you have undertaken thus far. We want to know whether you have taken advantage of the courses available to you in your school, and whether you have challenged yourself in advanced classes, and whether you have stretched yourself with outside-of-school educational opportunities […] Our strongest candidates have taken full advantage of what is available to them in their own schools.”

The natural solution seems to be to lower expectations and accept whatever college acceptances come with a reasonable amount of work and stress. However, DeLuca describes an obligation he has to himself to live up to an expectation of academic success he has set up throughout the past three years. The desire to validate that expectation compels him to take challenging courses and get into a certain caliber of college.

The belief that higher-ranked colleges lead to a higher chance of success affects this mindset, surely. However, it falls second to the belief that an acceptance to a selective school proves the student’s intelligence and gives meaning to the way they have poured themselves into their academics from day one.

“A lot of kids in AP classes, including myself, think that they are destined for a certain college, maybe that’s more selective, and I think that we can give that to ourselves, because we are smart. We’ve been told our whole lives ‘you have to get into a good college’ […] it’s ingrained into us,” DeLuca said.

In that sense, from the moment students begin to succeed in difficult courses, it creates a feed-forward cycle based on a personal measure of intelligence.

“It’s like college influences my classes, and then my classes influence the way that I think about myself. So it’s a kind of like a circle,” DeLuca said.

For Xu, her personal and peer expectations contribute to making intelligence a central part of her sense of self.

“People hear about me as someone who’s smart, and then I feel like without that, I don’t know exactly who I’d be in this community,” she said.

A Mindset That Compromises Health

DeLuca describes school as “overarching in [his] entire life” despite efforts to separate school and life with a part-time job and time with friends. In this sense, it is not just schoolwork but the mindset of school being paramount that creates tension for students.

In an environment where everybody cares immensely about grades, it is difficult to not get caught up in the frenzy.

Xu, who describes her friend group as composed almost entirely of top students in her grade, explains that nobody mentions classes or grades because it quickly hurts their relationships with one another.

DeLuca notes that classmates affect each others’ mindsets, and that the focus on grades overtakes all else in part because everybody else is doing it.

“When you get twenty kids together, who all think the same way and they’re starting to rub off on each other, that atmosphere is so toxic for someone’s mental health, where people are constantly worried about grades instead of their physical health,” said DeLuca.

DeLuca has tried to avoid this by maintaining his friendships with friends outside of his classes. Most of his classmates do not have enough time for a social life outside of their friendships with one another, he says. When even friendships are based in school and social interactions happen mainly in class, the importance of school over all else is once again reinforced.

Mental health is derived from physical health and social health, says DeLuca. He and Xu both make a conscious effort to spend a few hours a week with friends outside of school, though rather than sacrifice grades they sacrifice sleep.

“My sleep time is around midnight to 2 a.m. on normal days, but I’m not really willing to sacrifice my social life for that. So I just lose sleep, but that’s fine,” Xu said.

However, in his effort to keep his grades up while also maintaining a semblance of a social life, DeLuca explains that eating well and exercising fall to the wayside; he normally does not have time to make breakfast.

“I think nobody’s aware that it’s taking such a toll on their mental health until they start to vent about it and think about it. That’s when it dawns on them,” DeLuca said.

It is thus not the AP classes by themselves that affect students’ stress levels. It is that the workload and the desire to excel at any cost impact every aspect of student life and push out other components of a healthy lifestyle.

With classes, extracurriculars, and work, DeLuca is often not asleep until the early hours of the morning, though he considers himself diligent with his time. He explains that the vast majority of students with a mindset constantly focused on getting work done leads to burn-out.

“And because that constant working mentality in thought, it’s like a really good idea, and you think that it would work [amazingly]. But you don’t give yourself enough time for breaks, and you start to cripple basically with your mental health,” DeLuca said.

Solutions Moving Forward

Whether it be from teachers, counselors, or the student body, the school as a whole is taking measures to reduce academic stress.

The new homework policy, put into place this October, restricts homework at the AP level to four to five hours a week. However, at the AP level, controlling homework tends not to control workload much at all, since most students commit to hours of outside preparation per night or go far above expectations in order to maximize on success.

“If I put in four to five hours [a week per AP class], I could probably manage a B+ or an A- in a class. But that’s not what I’m looking for,” said Xu.

In the science department, teachers are taking efforts to reduce lab stress and give extra time to complete projects.

“You can move things [assignments] around. I can assign a video for homework to watch instead of a lab report. I’ve also given time during class to write the lab report. […] I think as much time as I give them during class, you know, give them a little bit of downtime or an extra day, and it helps alleviate some of the stress,” says AP chemistry teacher Timothy Knittel.

He continues to explain how he believes that at the end of the day, mental health should be weighed against the stress AP classes induce.

“I think mental health is more important than anything else, more important than grades. If I feel that I need to give the class a day off, if they [the class] came and said they needed the day off, I’d say, ‘okay, you can have the day off.’”

Knittel cannot control the number of difficult classes students take, but he can control the way he teaches his class. He does not have a hands-off attitude towards student stress; he does his utmost to communicate with his students and accommodate them.

“I really try to listen to what they’re saying and try to empathize with them. I try to be accommodating when I can,” he said.

Knittel tries to be someone students can approach when they need the assistance rather than the students feeling like there is no point in asking for any extensions, or that the teacher will change his or her opinion of the said student if such accommodations are asked for.

However, classes must strike a fine balance between lessening stress and maintaining success on the national AP Exam or in college courses.

In the math department, for classes like AB and BC Calculus, reducing workload is possible only to a certain extent.

“Overall, the math department is trying to cater to as many students as possible in trying to create the best syllabus possible that will allow each student to prepare themselves appropriately. Although efforts are being taken to make the course suitable to each student, there are some times when the stress that comes with the exams is crucial for an individual’s understanding of the concept, as well as thinking quickly in a test environment,” said Lisa Gartner, who teaches both AP calculus courses at WA. “I’m trying to prepare students for the AP exam where I don’t know what the questions are going to be. […] My primary focus is getting them [students] to have a strong foundation.”

However, Gartner has been cutting homework problems from many of her assignments in keeping with the new homework policy to reduce busywork. She stresses the importance of student-teacher communication, explaining that she does not always know if an assignment causes undue stress or if students are spending several hours on work a night.

Despite these efforts to reduce stress, some students, like Xu, are willing to take on any workload in order to succeed.

“Without all these stresses and difficulties, I wouldn’t be as strong of a student as I am right now,” she said.

DeLuca has lost much of the passion for learning that he had going into high school. At the tail end of his high-school education, he is exhausted.

“I’ve never been more burned out than I have been at this point in my senior year. I feel like, I don’t know, I just don’t want to do schoolwork anymore […] at the end of the day, I’m just like, ‘is this worth it?’” he said.