WA staff manages mental health

January 20, 2019

Depression and anxiety have become more and more common in teenagers in today’s fast-paced lifestyle. Stress concerning academics, extracurriculars, social situations, and life at home often build up and overwhelm students.

In Massachusetts, 25.5 to 29.4 percent of high school students feel depressed. Additionally, 2.2 to 3.6 percent of those students have attempted suicide or harmed themselves.

Westford Academy is a high-performing school with a variety of classes and extracurriculars that students become a part of. As beneficial as that might be, students often get overwhelmed and can experience symptoms of anxiety or depression.

“I do believe that our students are stressed. I worry about it all the time,” Guidance Counselor Wendy Pechacek said.

The last student suicide that WA experienced was before Pechacek became a guidance counselor, which was eighteen years ago. Surrounding communities, such as Acton-Boxborough, have seen recent suicides, and Pechacek expressed how grateful she is that WA has not gone through the same situation recently. However, a number of WA students are hospitalized due to mental health.

According to Micaela Violette, one of WA’s social workers, students have certain coping capacities for stress, and need coping strategies and support networks to rely on.

“We all experience stress in our lives, different levels of stress, and I think you have some students who can manage it and some who can’t,” Violette said.

Coping strategies include physical activity, distractions from what is stressing them out, regulating breathing, and self-care, such as getting adequate sleep and nutrition. Furthermore, Violette believes that having a trusted adult to talk to is highly beneficial.

“I think the number one thing is to talk to an adult, and I think a lot of times teens want to go to their friends, which makes sense, and I think that that can be helpful, but certainly people are reaching the level in which they are thinking about hurting themselves, they should absolutely talk to an adult,” Violette said.

Pechacek agreed, saying that the most stressed students are those who hear from other students about their problems.

“The students that get overwhelmed are often the ones that everyone else brings their problems to,” Pechacek said.

Violette also recommended that students put aside time to do something that is relaxing or enjoyable to them. However, according to the results from the Challenge Success Survey Results in 2016, this is increasingly difficult for students to do. 50 percent of students reported that they dropped an activity due to academic workload, 64 percent said they did not spend enough time with family friends, and 66 percent do not get enough sleep.

According to Pechacek, the fact that students talk about schools and grades often adds to their stress. One of her goals with Challenge Success is to reduce that conversation to focus on accomplishments.

“I think we have a culture where people feed into each other and build [the stress] up,” Pechacek said.

Additionally, students place a lot of pressure on themselves or face pressure from family and peers, which can also lead to clinical depression or anxiety. For these reasons and more, a number of WA students have been hospitalized due to mental health. According to Violette, multiple factors from and outside of school play into depression and anxiety.

“In my experience, it’s not usually one thing that contributes to someone being suicidal or someone needing a hospitalization. It’s usually a bunch of different factors depending on the person I think. For some students, school can play a role you know, stress around […] so many students have a lot of different things on their plates, whether it’s extracurricular activities, you know, wanting to excel at school, do really well academically, pressures they might experience from their families or the pressures they put on themselves or their friends to keep up with everyone and be successful, so I think that that can lead students to experience a lot of anxiety, or people who put high expectations on themselves, they don’t meet those, can feel really sad and disappointed about it,” Violette said.

There have been steps taken to recognize any signs of clinical depression in students. In seventh grade, students are given information on depression and then take an emotional well-being survey. Those with higher scores on the survey have one-on-one meetings with their guidance counselors. In ninth grade, the mandatory health curriculum includes a program called “Breaking Free From Depression” followed by another survey, where about 12 percent of freshmen have meetings with their guidance counselors because of high scores.

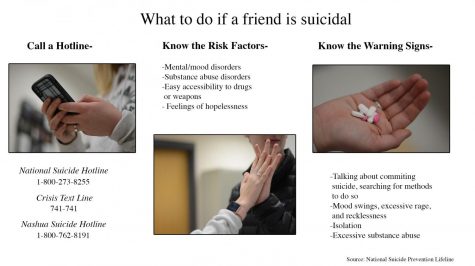

On December 19, Pechacek sent out an email with a crisis text line for students and posted it around the school as well. It is an anonymous hotline for suicide prevention that students can call if they need to talk to someone.

“Those are in place specifically to help us identify students. It’s also to help us help students identify other students, so a big part of those curriculums is to teach you all how to be part of a safety net, because most of the time when we hear about a student that’s in crisis, it’s from another student,” Pechacek said.

To help students ease back into school after long-term absences, the Bridge Program was put into place as an option for students. Pechacek is in charge of the program, while Violette is the social worker involved and English teacher Michael Estabrook is the academic coordinator.

When Pechacek started working at WA, there were 46 students hospitalized for various reasons, and the school did not have a way for alleviating stress after they returned from their long-term absences. The Bridge Program was then put in place. The hospitalizations in recent years have been cut in half and are consistent, with 22 in 2015, 24 in 2016, and 23 in 2017. The hospitalizations are usually due to concussions, surgeries, and mental health.

When students return to school after long-term absences, they have a meeting with their guidance counselor, dean, a social worker or school psychologist, and their parents. If the student chooses to use Bridge, Estabrook is present as well. During the meeting, a plan is created to allow the student enough time to adjust so that they are not under overwhelming stress when they return to class. There is no limit to how long they can stay in the Bridge program.

“It’s not like ‘you have to go back now.’ We’ve had students who are there for a couple weeks, we’ve had students who have continued to use it for a couple months, where they will be back in all their classes but their DLT block will just be in Bridge, or they won’t go to PE, continue to have a block in Bridge. So it varies depending on the student,” Estabrook said.

This is Estabrook’s fourth year handling the Bridge program, having started during his second year at Westford Academy. He has noticed changes in how many students need to use the program every year. In the previous years, Estabrook had a lot of students in Bridge due to mental health. As of December 2018, he saw a more mix in the program with students hospitalized for surgeries, concussions, and mental health.

“When I first started, I feel like we had a lot more. Last year was pretty quiet with periods of high numbers. This year’s been extremely quiet, we didn’t get our first student till the end of October, when usually we get kids already in September,” Estabrook said.

Even if students are not hospitalized because of clinical depression or anxiety, they often can develop them after being hospitalized for concussions due to increased stress or having to leave activities.

“If students have a concussion, and [there is] a sport that they have given their all to, you know, over the years, been playing since they were little and thought that was the thing they were going to do and then all of a sudden they can’t do it and they don’t know if they’re going to be able to do it again, that can definitely have an impact,” Pechacek said.

According to Violette, multiple social and academic pressures can factor into anxiety or depression, both in and out of school. For example, Estabrook mentioned that the Bridge program has had students with depression as a result of gender identity or sexual orientation, as well as school-avoidant students. The school-avoidant students use Bridge for a more relaxed environment where they do not have to be in a larger class.

“There’s overlap. All these things kind of mix together, so they could be stressed about school but it’s also mixed in with general anxiety […] the school stress could make it worse, exacerbate it, so it’s hard to say it’s only because of school,” Estabrook said.

Suicides and hospitalizations due to mental health are never caused by one singular factor, rather a combination of multiple stressors.

“It would be easier if we could point to an exact trend, right, but I think the thing with mental health is that it doesn’t discriminate. So it’s not just our high achieving students or our low achieving students or all girls or all boys, even grade wise, it really fluctuates. Mental health does not discriminate,” Violette said.