Activist students reflect on equality, growth, and change

April 14, 2018

On February 26, 2017, Westford Academy student Medha Palnati stood on the steps of the Boston Common as she delivered the final words of her speech at the Emergency Rally to Stand for Democracy to rally for truth and transparency in government:

“It is our duty to preserve what is true. […] This rally is one act of resistance. Hear our voices. Hear them.”

Palnati is one of a few students at Westford Academy who have made their purpose to make their voices heard and their ideals made reality. Alongside Palnati, seniors Prachi Jhawar, Robin Miller and Alice Yun are student activists whose work in social justice stands out in the community. Miller is the co-leader of the Gender and Sexuality Alliance and Vice-President of NOW Club, Palnati is the Co-President of Human Rights Club and a youth leader for the Lowell-based organization History Unerased, Yun is President and founder of NOW Club, and Jhawar is Co-Leader of Human Rights Club. They are also widely involved in social activism outside of school; all four girls participate in rallies and marches, and Palnati has spoken at the Emergency Rally to Stand for Democracy as well as the Massachusetts Trans Political Coalition rally. Palnati, Miller, and Jhawar also led the creation of Diversity Day and were members of the organizing team of the recent walkout.

What does social activism really mean in the context of high school and what made it the focus of these girls’ high-school years? What inspires, drives, and challenges them, and where will the steps they are taking lead?

Jhawar, Miller, and Yun, with NOW adviser Laine Winokur, stand in the pose of the famous WW II “We Can Do It” poster.

Faces of a generation

Jhawar, Miller, Palnati, and Yun stand out at Westford Academy, but are part of a broader movement of student activism sweeping the country. Although the four of them have been politically involved since their freshman year in 2014-2015, several of the projects they have been involved in — the walkout and Diversity Day, most notably — were spurred by events that caused high-schoolers from across the country to look up and take action.

In the wake of the Parkland shooting, students in more than 3,130 schools walked out in protest of gun violence. Even before that, high-schoolers took to the podium to protest motions such as the immigration ban in January of 2017. A survey by Kaplan Test Prep in 2018 polled 567 future college students across the country and found that 76% indicated a higher interest in politics, social justice, and/or activism as compared to in 2016.

The girls know they are far from alone when it comes to social activism on the student level.

“There’s always another group of people, whether you’ve met them or not, there’s someone there supporting you […] As much as we like to think we’re unique, other people have the same ideas as we do. They’re just different — they’re just not in the same concentrated place,” Jhawar said.

But within the halls of WA, these four girls represent the face of the social justice movement, and with their impact on a local level, we are reminded of the magnitude and gravity of student activism not just in regards to the country’s progress but on our own school’s steps forward.

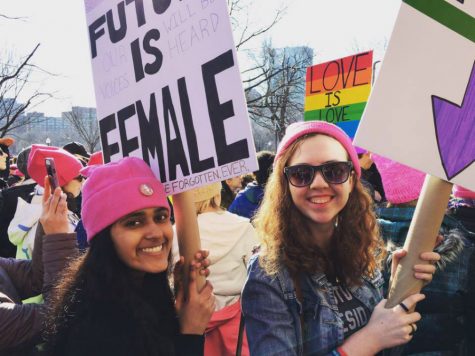

Jhawar and Miller at the Women’s March 2017.

Where it all started

Despite the rise of protest movements throughout the country, the number of students who actively and regularly participate in student activism is still comparatively few. Jhawar, Miller, Palnati, and Yun’s unique drive stems from their personal conceptions of justice. Although all four of them were aware of concepts like equality since childhood, it was only in high school that they began to explore the extent and flaws of those concepts in the world around them.

“As a child, you’re like “everything’s fair”, you have to share among your friends — but then as you start to grow up, you realize that things aren’t quite so black and white. You realize that there are certain disadvantages that women get, that people of color get, […] that LGBT people get, people with disabilities, so on and so on and so on, that the world sees and the the world treats unfairly. Just seeing that inherently frustrates me, just as who I am,” said Miller.

It is this inherent frustration with the status quo that is common in all four girls’ stories of becoming involved in activism. For Palnati, anger about “being born a girl” in a world where women face many obstacles eventually fueled her commitment to social justice. Jhawar’s insistence on compassion as a child coupled with online research throughout the years led to her developing an identity as a feminist, and similarly, Yun sensed an underlying unfairness in general interactions with family and community that led to her involvement in feminism.

However, their level of commitment is not just a product of their personal ideals and drive but their influence on one another. Yun, for instance, knew she was a feminist since ninth grade, but believes that she probably would not have spoken out for women’s rights and social justice in general if she had not connected with like-minded students.

“I just think that it’s really helpful to know that you have people who have your back and people who identify in certain groups — that really puts everything together,” she said.

Palnati agrees, adding that she either would not have begun certain initiatives or given up halfway if she had been the sole student activist in her grade level. In this sense, their friendship serves the dual purpose of allowing them to be comfortable in their identity but also allowing them to realize their goals.

“Unfortunately, social activism is kind of hard. It’s hard to to put ideas out there because it’s kind of like throwing darts at a dartboard and hoping they stick because we, like I said, we live in a society where so much of it is frowned upon and everyone has different paths that they want to achieve the same goals […] if you don’t have a support group, you lose sight of the end goal,” Palnati said.

High-school activism

College students are much more likely than high school students to participate in campus protests and be politically involved, and are generally taken more seriously when they do so. This is due to a combination of factors: the fact that high-schoolers often cannot bring conceptions or ideals into action, the inability of high-schoolers to vote, and the belief of adults that high-schoolers are too young to have informed beliefs.

Laine Winokur, the history teacher who advises the girls in NOW club, speaks to the first point and how it makes the girls’ student activism successful: they have the ability to follow through. She cites multiples instances where they have implemented a direct solution to a problem that they saw in the school — some examples including the female hygiene products in the bathrooms last year and Diversity Day in these past few months — and explains that this quality is rare in teenagers.

Part of the reason why students may not follow through on ideals is because those ideals are only vaguely conceived and unimportant in their day-to-day lives, seeing as teenagers have a limited impact on politics until they are eighteen and can vote. In general, teenagers are considered to parrot the beliefs of influential figures rather than have their own worldview.

Jhawar, who supports lowering the voting age to sixteen, mentions that many adults believe that younger teenagers will not have informed opinions or individual beliefs. However, being politically aware at a young age solves not only that issue but the issue of adults also voting based on limited knowledge.

“There’s so many people who go into voting at the age of 50 and they’re completely blind and they just pick something because it makes sense or because they agree with the [political] party, even though their ideas might not even be the same,” she said.

Winokur believes that student activism allows students to see the lessons they have learned in the classroom in a bigger context as well as apply skills like debate and discussion to current issues.

“I think it’s awesome that they don’t think that high school is preventing them from following whatever their passions are […] Any students that can take any lessons they have learned […] and sort of see it in a bigger context, that’s the goal for a lot of teachers.”

Winokur adds that since this generation will be the ones enacting change in the future, it is important for adults to embrace teenage movements for change.

“I think oftentimes, we need to listen to you all more, because you’re going to be pushing us forward,” she said.

Jhawar stands with a poster at the 2018 Women’s March

Pushing back against a resistance to change

As Palnati says, social activism can be difficult — and those words certainly ring true for the initiatives she, Miller, Jhawar, and Yun have organized over their years in high school. Several of their projects have attracted criticism that affects not only the project itself but their day-to-day-life.

“A lot of people have pinpointed me to specific events and have disliked me a lot because of those events. I used be able to smile at them in the hallway and now I can’t because they won’t even look at me, and that’s something I’ve had to deal with. But I understand that I’m doing what, for me, I think is the right thing to do,” said Jhawar.

For Palnati, WA’s recent Diversity and Inclusion Day has been a significant cause for self-doubt. Despite general support, some students, parents, and faculty have criticized the event. However, she has found that it forced her to question the merit of what she was doing, which led her to reaffirm that the path she was taking was the right one to her.

“Of course people are going to criticize you but tell me, is there a better solution to the issues at your school? Is there a better solution to helping fight racism at Westford Academy?” she said.

The criticism the girls have faced comes in part from those who believe that these initiatives are over the top and that things are fine as they are. Referring to this mindset, Miller speaks of a “blindness and complacency” that she sees in society that she believes is essential to overcome.

However, with the stress and high demands of high school, doing anything beyond the bare minimum is often a tall order. While those like Jhawar, Miller, Palnati, and Yun are passionate enough about social justice to make it a focal point of their high school experience, most students choose to remain passive even if they support social change because they do not have the mental energy or commitment to challenge the norm.

Miller explains that most students are just “trying to get through the day”, and any issues that may bother them are pushed to the wayside. She cites this as a major reason for why high-schoolers might resist change: it’s not that they are necessarily opposed to it, but there are simply more immediate issues preoccupying them. The emotional toll it takes, though, is severe.

“But it eats at you. It eats away at you and that just makes everything worse as you start, as you try to ignore things, whether you’re talking about social activist issues or other things that you are passionate about, if you don’t step up and confront them. And so the most important thing for people to do is to say, ‘you know what, this might think make things [better] in the long run’,” Miller said.

Moving forward

In the end, though, high school is a fraction of life that only grows smaller with time as the future expands. Moving into college prospects and eventually the working world, the girls all seek to integrate social justice into their futures in ways that align with their personalities and abilities.

Jhawar is headed to American University in the fall to double major in economics and political science with a minor in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, while the other three have yet to commit.

Miller and Jhawar are both aiming to be politicians, but assert that they will be supporting each other even if their careers intersect.

Palnati and Yun, on the other hand, both want to be doctors. Though their choice might seem contrary to their history of social activism, for both of them, medicine falls in line with their personal preferences and goals.

“I firmly believe that like there are ways in every profession to help people and that’s why we work, you know, we work for a better society […] [in policy] I would get lost very quickly, not seeing a concrete change,” said Palnati, who aspires to work for Doctors Without Borders.

Yun did not want to be a doctor as a freshman, but expanded her perspective in part due to her experience with activism.

“As a junior, I thought [medicine] was more mostly oriented towards like study and knowledge of the human body. […] As I became more involved in social activism I began to realize that in medicine, understanding patient interactions is such a necessity, and how that can sometimes come into play with their background — language, economic status, and things like that,” Yun said.

In the end, though, all of them emphasize the impact that social activism has had and will continue to have on their lives. The mindset of working for change and a deeply ingrained sense of compassion have largely directed their approach to their futures.

The wheels of progress have begun to turn on the local and national levels alike, and Winokur’s hopes for the girls speak to the importance of perpetuating change.

“I just hope that whatever they end up doing, they cause change, because I think that’s their goal […] and once they’ve caused that change, come back here and share those lessons with future generations of WA students to help keep that cycle going,” Winokur said.